Karin Hawkinson

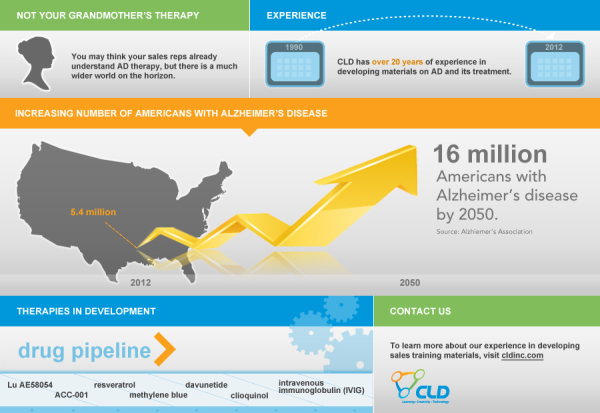

The Alzheimer’s Association predicts that the number of Americans with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) will balloon from the current 5.4 million to 16 million by 2050. In response to this looming health, social, and economic crisis, researchers are moving beyond the therapy that has been the focus for the last 2 decades to new agents that target the reasons AD is thought to occur in the first place.

Tacrine, the first agent approved for the treatment of AD, entered the market in 1993. One of the deficits observed in AD is a decrease in acetylcholine, one of the neurotransmitters (chemical messengers) that allow nerve cells to communicate, and tacrine helped to increase the amount of acetylcholine in the brain. Since that time, every AD product that has entered the market has also targeted levels of chemical messengers. Aricept® (donepezil), Razadyne® (galantamine), and Exelon® (rivastigmine) also increase acetylcholine levels, while Namenda® (memantine) affects glutamate levels.

However, it is generally acknowledged that reduced levels of neurotransmitters are not the actual cause of AD, merely a result of the sticky plaques and tangles of tau protein that build up in AD brains, slowly killing the nerve cells. This discrepancy is why currently available agents improve symptoms over the short-term but have not been able to stop the progression of AD.

Click to enlarge image

A number of agents that are directed at potential causes of AD are in clinical development, although there have also been significant obstacles. One group of agents are antibodies that are designed to dissolve plaques or prevent them from forming, and these include bapineuzumab, solanezumab, and crenezumab. However, bapineuzumab recently failed to meet its endpoint in a large clinical trial of AD patients and was pulled from development. Solanezumab also failed to meets its primary endpoint in 2 recent trials and the developers are in discussion with regulators about the agent’s future. Some researchers theorize that once people actually show AD symptoms, their brains may be too damaged to rescue. In hopes of addressing this issue, crenezumab will be tested in healthy people at high genetic risk for AD.

Some other therapies are also in development, including:

- intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), a mixture of antibodies whose potential mechanism in AD is unknown

- clioquinol, which is thought to target plaques

- davunetide, which is thought to target tau protein

- methylene blue, an agent already used for malaria and staining tissue that may target tau protein

- resveratrol, a naturally occurring compound that is thought to protect nerve cells

- Lu AE58054, a serotonin type 6 (5-HT6) receptor antagonist

- ACC-001, a second-generation vaccine that stimulates the body to produce its own antibodies to plaque

So while you think your sales representatives may already understand AD therapy, a much wider world is on the horizon. To learn more about our experience in developing sales training materials for leading pharma and biotech companies on AD and its treatment, click here.